Groupthink

This book helped me understand modern politics better

Why We’re Polarized is a fascinating look at human psychology.

When I meet someone who plays bridge, I feel an immediate affinity for them. It's not because I really know anything about them beyond their taste in card games. For all I know, we could be like oil and water once we actually start talking. But we both love bridge, and that makes me more likely to connect with someone.

There are few forces stronger than the power of group identity. The groups we self-identify as are a key part of who we are. Most of the time, these identities aren’t inherently positive or negative—but each one of them shapes the way we see the world.

In his terrific book Why We’re Polarized, Ezra Klein argues that identity is the answer to the question suggested by his title. The phrase “identity politics” has been thrown around a lot in recent years—usually in a negative context—but Klein explains that it’s human instinct to let our group identities guide our decision making. “A group can know more and reason better than an individual,” he says, “and thus human beings with the social and intellectual skills to pool knowledge had a survival advantage over those who didn’t.”

Why We’re Polarized is fundamentally a book about American politics, but I thought it was also a fascinating look at human psychology. One of my main takeaways was that many of us might need to reframe how we think about changing someone’s mind. I’m a data person (another identity I have!), so my instinct is always to use numbers and logic to convince people of something. When I meet someone who disagrees with me, I tend to explain the merits of my position and compare results of the two different approaches.

But Why We’re Polarized makes it clear that group identity can overrule any argument for or against an issue. If you want to bridge the gap, it’s more productive to appeal to someone’s identity than to their logic.

This is especially true for political issues. Klein explains how political identity used to be more rooted in where you lived rather than what party you belonged to. (This wasn’t always a good thing: He devotes an entire chapter to the damaging influence of the Dixiecrats.) The parties themselves were seen more as shortcuts you could use to inform your choices. “We may not know the precise right level of taxes… but we know whether we support the Democratic, Republican, Green, or Libertarian party,” Klein says.

Americans tended to vote for candidates who made the most sense for where they lived rather than whether they were a Democrat or Republican, which led to a lot more ticket splitting. Between 1972 and 1980, 46 percent of voters in contested districts voted for a different party House candidate from who they supported for president. By 2018, only 3 percent of voters did.

What changed? The political parties themselves. For a lot of different reasons—starting with the fight for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and including the rise of cable news—both parties have to varying degrees adopted more extreme positions over the last several decades. As a result, the party identities themselves have become more polarized and caused people to dig in more firmly.

I was especially interested to read what Klein had to say about the relationship between social media and polarization. The internet gets a lot of criticism for how it has divided us, but people were seeking out media that corresponded to their political affiliation well before social media. At the same time, it is undeniable, that its ability to connect the fringes of the parties together has exacerbated the situation. When you look at something like January 6th, it’s clear that the internet played a role in enabling the most extreme people to find each other and organize.

Overall, though, Klein thinks that our polarization problem goes much deeper than just social media. He’s quite persuasive, and I agree with him. Like most books, he is much better about diagnosing the problem and educating us on the historical context than he is at offering solutions. Klein has a couple ideas about improvements we could make—such as restructuring the Supreme Court or changing the Electoral College—but he acknowledges none of them are a true solution.

At the end of last year, I said that one of my plans for 2022 was to read more about polarization. It’s a problem I’m quite concerned about, and this helped me understand the phenomena much better. I wouldn’t say I finished the book more optimistic about our ability to tackle the problem, which is even more daunting than I thought. But if you want to understand what’s going on with politics in the United States, this is the book to pick up.

Food for thought

What it will really take to feed the world

In his latest book, one of my favorite authors argues that solving hunger requires more than producing more food.

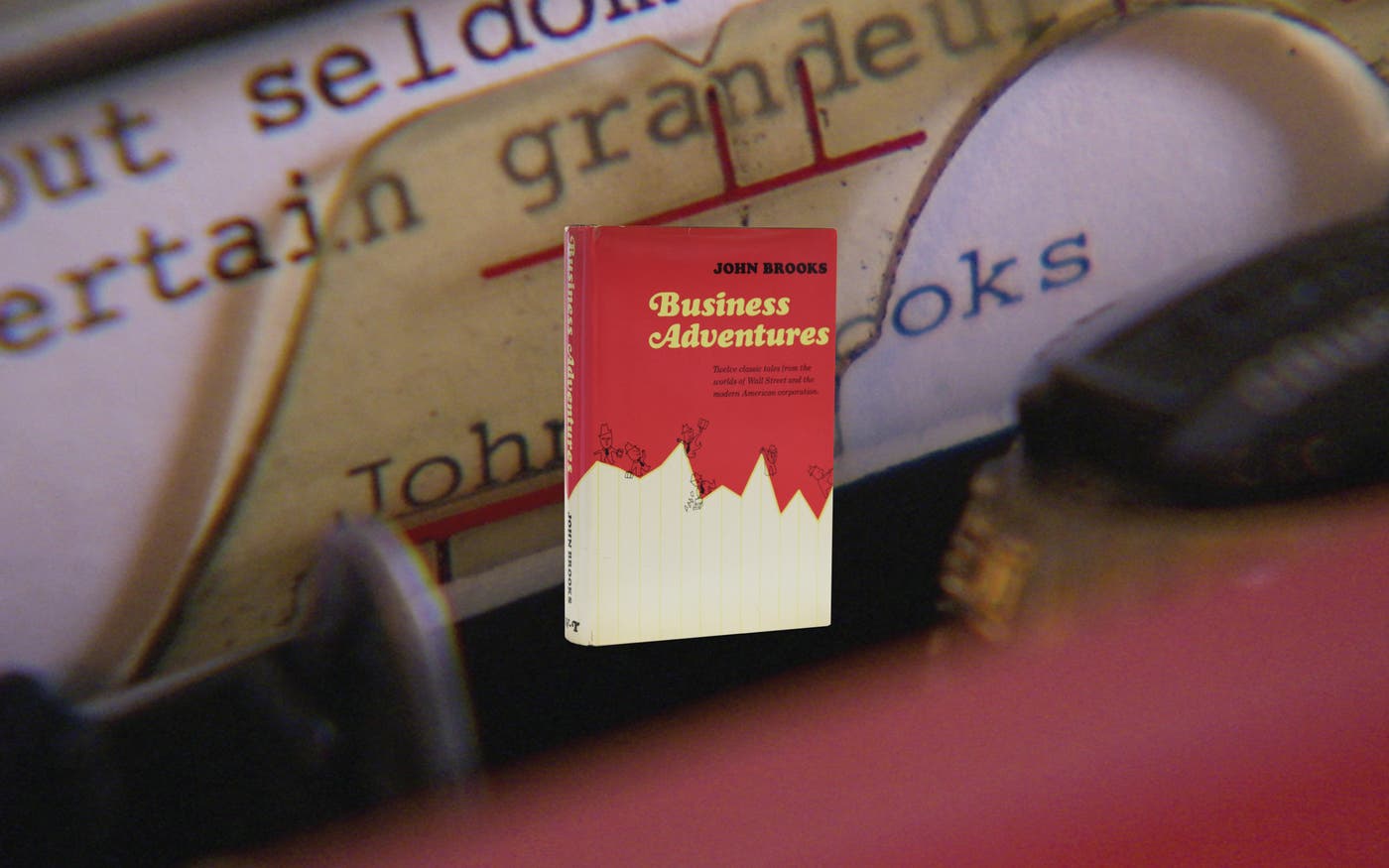

In the introduction to his latest book, How to Feed the World, Vaclav Smil writes that “numbers are the antidote to wishful thinking.” That one line captures why I’ve been such a devoted reader of this curmudgeonly Canada-based Czech academic for so many years. Across his decades of research and writing, Vaclav has tackled some of the biggest questions in energy, agriculture, and public health—not by making grand predictions, but by breaking down complex problems into measurable data.

Now, in How to Feed the World, Vaclav applies that same approach to one of the most pressing issues of our time: ensuring that everyone has enough nutritious food to eat. Many discussions about feeding the world focus on increasing agricultural productivity through improved seeds, healthier soils, better farming practices, and more productive livestock (all priorities for the Gates Foundation). Vaclav, however, insists we already produce more than enough food to feed the world. The real challenge, he says, is what happens after the food is grown.

This kind of argument is classic Vaclav—questioning assumptions, forcing us to rethink the way we frame problems, and turning conventional wisdom on its head. His analysis is never about the best- or worst-case scenarios; it’s about what the numbers actually tell us.

And the numbers tell a striking story: Some of the world’s biggest food producers have the highest rates of undernourishment. Globally, we produce around 3,000 calories per person per day—more than enough to feed everyone—but a staggering one-third of all food is wasted. (In some rich countries, that figure climbs to 45 percent.) Distribution systems fail, economic policies backfire, and food doesn’t always go where it’s needed.

I’ve seen this firsthand through the Gates Foundation’s work in sub-Saharan Africa, where food insecurity is driven by low agricultural productivity and weak infrastructure. Yields in the region remain far lower than in Asia or Latin America, in part because farmers rely on rain-fed agriculture rather than irrigation and have limited access to fertilizers, quality seeds, and digital farming tools. But even when food is grown, getting it to market is another challenge. Poor roads drive up transport costs, inadequate storage leads to food going bad, and weak trade networks make nutritious food unaffordable for many families.

And access is only part of the problem. Even when people get enough calories, they’re often missing the right nutrients. Malnutrition remains one of the most critical challenges the foundation works on—and it’s more complex than eating enough food. While severe hunger has declined globally, micronutrient deficiencies remain stubbornly common, even in wealthy countries. One of the most effective solutions has been around for nearly a century: food fortification. In the U.S., flour has been fortified with iron and vitamin B since the 1940s. This simple step has helped prevent conditions like anemia and neural tube defects and improve public health at scale—close to vaccines in terms of lives improved per dollar spent.

One of the most interesting parts of the book is Vaclav’s exploration of how human diets evolved. Across civilizations, people independently discovered that pairing grains with legumes created complete protein profiles—whether it was rice and soybeans in Asia, wheat and lentils in India, or corn and beans in the Americas. These solutions emerged from practical experience long before modern science could explain why they worked so well.

But just as past generations adapted their diets to available resources, we’re now facing new challenges that require us to adapt in different ways. Technology and innovation can help. They’ve already transformed the way we produce food, and they’ll continue to play a role. Take aquaculture: Once a tiny industry, it’s grown over the past 40 years to supply more seafood for the world than traditional fishing—a scalable way to meet global protein demands. The Green Revolution is another example. Beginning in the 1960s, innovations in higher-yielding crops, more effective fertilizers, and modern irrigation prevented widespread famine in India and Mexico. These changes were once seen as unlikely, too.

New breakthroughs could drive even more progress. CRISPR gene editing, for instance, could help develop crops that are more resilient to drought, disease, and pests—critical for farmers facing the pressures of climate change. Vaclav warns that we can’t count on technological miracles alone, and I agree. But I also believe that breakthroughs like CRISPR could be game-changing, just as the Green Revolution once was. The key is balancing long-term innovation with practical solutions we can implement immediately.

And some of these solutions aren’t about producing more food at all—they’re about wasting less of what we already have. Better storage and packaging, smarter supply chains, and flexible pricing models could significantly reduce spoilage and excess inventory. In a conversation we had about the book, Vaclav pointed out that Costco (which might seem like the pinnacle of U.S. consumption) stocks fewer than 4,000 items, compared to 40,000-plus in a typical North American supermarket.

That kind of efficiency—focusing on fewer, high-turnover products—reduces waste, lowers costs, and ultimately eases pressure on global food supply, helping make food more affordable where it is needed most.

How to Feed the World had a lot to teach me—and I’m sure it will teach you a lot, too. Like all of Vaclav’s best books, it challenges readers to think differently about a problem we thought we understood. Growing more and better food remains crucial—especially in places like sub-Saharan Africa, where there simply isn’t enough. But as the world’s population approaches 10 billion, increasing agricultural productivity alone won’t solve hunger and malnutrition. We also need to ensure that food is more accessible and affordable, less wasted, and just as nutritious as it is abundant.

After all, the goal isn’t to make more food for its own sake—it’s to feed more people.

History and their story

A memoir of love and politics in the 1960s

I loved—and finished—Doris Kearns Goodwin’s An Unfinished Love Story.

I picked either the best time or the worst time to read Doris Kearns Goodwin’s new memoir. As I finished it, I was also deep in the writing of my first autobiography. On one hand, reading a book as thoughtful and well written as An Unfinished Love Story inspired me to push myself even more as an author. On the other hand, Goodwin sets a daunting example. Trying to write as well as she does is like trying to sing along with Lady Gaga.

I’m a big fan of Goodwin’s—Team of Rivals is one of my favorite history books ever—so I wasn’t surprised that An Unfinished Love Story was so compelling. It starts with a clever conceit. Doris was married for 42 years to Dick Goodwin, a policy expert and White House speechwriter who played a crucial role in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations of the 1960s. Toward the end of Dick’s life, he and Doris started going through 300 boxes of papers and memorabilia he had collected—an exercise that led them to reopen an old debate about the relative merits of the two presidents, and especially the question of which man deserves more credit for the accomplishments of the Great Society.

The book is partly about Doris and Dick’s decades-long relationship, and partly about a pivotal time in American history. It works on both fronts.

I had never heard of Dick Goodwin before I read the book. I did know about Ted Sorensen, who had a major influence on Kennedy’s thinking and speeches; Dick Goodwin, it turns out, was just as important. He helped shape the Great Society, the most dramatic shift in America’s public safety net since Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. He was a senior advisor on Bobby Kennedy’s presidential campaign, and many years later, drafted Al Gore’s statesmanlike concession speech after the 2000 election. (Goodwin also led the investigation in the real-life game-show scandal that was the subject of the movie Quiz Show; he’s played by Rob Morrow.)

The book left me with more admiration for both Kennedy and Johnson. When the Goodwins began the project of going through Dick’s papers, each had clear opinions on the two presidents: Dick was a Kennedy guy who quit the Johnson administration in protest over the Vietnam war and the president’s domineering style, while Doris preferred Johnson’s political savvy and ability to get things done. She worked at the White House during the latter’s administration and became a confidante; after he left office, she went to Texas to help him with his memoir.

Sadly, the Goodwins’ project was cut short by Dick’s death in 2018. In the end, he and Doris came to see both presidents in a more nuanced way. After reading the book, so did I. Doris takes you behind the scenes so you can watch the two presidents and their teams figure out how to move their agenda forward, recruit good people, and explain their plans to the public. At the same time, she doesn't shy away from the contradictions and flaws in their characters, particularly in LBJ's case.

Doris’ personal experiences, and her retelling of Dick’s, make the history feel more real. She’s not just reporting on what happened—she can tell you what it was like to be there, using intimate personal details to bring the era to life in a way I hadn’t seen before. In one funny and revealing moment, Johnson complains that Dick Goodwin is getting too much attention from the media—to the point that he tells a reporter that no one by that name even works at the White House.

I think this book will resonate with a lot of different readers. For one thing, it’s hard to deny the similarities between the 1960s and today—a time of political upheaval, generational conflict, and protests on college campuses. Whether you already know a lot about the ’60s or you’re just dipping your toe into those waters, whether you want a deep dive into the art of political writing or a charming story about a married couple who adored each other, you’ll get it from An Unfinished Love Story.

Gen angst

The cost of growing up online

The Anxious Generation explains how smartphones and social media rewired a generation.

Growing up, I was always going down rabbit holes to explore whatever caught my interest or captured my curiosity. When I felt restless or bored—or got in trouble for misbehaving—I would disappear into my room and lose myself in books or ideas, often for hours without interruption. This ability to turn idle time into deep thinking and learning became a fundamental part of who I am.

It was also crucial to my success later on. At Microsoft in the ’90s, I began taking an annual “Think Week,” when I would isolate myself in a cabin on Washington’s Hood Canal with nothing but a big bag of books and technical papers. For seven days straight, I would read, think, and write about the future, interacting only with the person who dropped off meals for me. I was so committed to uninterrupted concentration during these weeks that I wouldn’t even check my email.

Reading Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation has made me wonder: Would I have developed this habit if I had grown up with today’s technology? If every time I was alone in my room as a kid, there was a distracting app I could scroll through? If every time I sat down to tackle a programming problem as a teenager, four new messages popped up? I don’t have the answers—but these are questions that everyone who cares about how young minds develop should be asking.

Haidt’s book, about how smartphones and social media have transformed childhood and adolescence, is scary but convincing. Its premise—that starting in the early 2010s, there was a “great rewiring” of an entire generation’s social and intellectual development—was interesting to me in part because I saw it happen in my own house. When my oldest daughter (a pediatrician who recommended the book to me) was in middle school, social media was present but not dominant. By the time my younger daughter reached adolescence six years later, being online all the time was simply part of being a pre-teen.

What makes The Anxious Generation different from other books on similar topics is Haidt’s insight that we’re actually facing two distinct crises: digital under-parenting (giving kids unlimited and unsupervised access to devices and social media) and real-world over-parenting (protecting kids from every possible harm in the real world). The result is young people who are suffering from addiction-like behaviors—and suffering, period—while struggling to handle challenges and setbacks that are part of everyday life.

My childhood was marked by remarkable freedom—something that might surprise people who assume I spent all day glued to a computer indoors. I went hiking on trails that would terrify today’s parents, explored endlessly with neighborhood friends, and ran around Washington D.C. during my time as a Senate page. When I was in high school, Paul Allen and I even lived on our own for a few months in Vancouver, Washington, while working as programmers at a power company. My parents didn’t know where I was half the time, and that was normal back then. While I got hurt on some of these adventures and got in trouble on many others, these experiences were more beneficial than bad. They taught me resilience, independence, and judgment in ways that no amount of supervised, structured activity could replicate.

It wasn’t all fun and games, but I had what Haidt calls a play-based childhood. Now, a phone-based childhood is much more common—a shift that predated the pandemic but solidified when screens became important tools for learning and socializing. The irony is that parents these days are overprotective in the physical world and strangely hands-off in the digital one, letting kids live life online largely without supervision.

The consequences are staggering. Today’s teenagers spend an average of six to eight hours per day on screen-based leisure activities—that is, not for schoolwork or homework. The real number might actually be much higher, given that a third of teenagers also say they’re on a social media site “almost constantly.” For the generation Haidt writes about, this has coincided with sharp spikes in anxiety and depression, higher rates of eating disorders and self-harm, plummeting self-esteem, and increased feelings of isolation despite more around-the-clock, on-demand connection than ever. Then there are the opportunity costs of a phone-based childhood that Haidt documents: less (and worse) sleep, less reading, less in-person socializing, less time outside, and less independence.

All of this is concerning, but I’m especially worried about the impact on critical thinking and concentrating. Our attention spans are like muscles, and the non-stop interruptions and addictive nature of social media make it incredibly difficult for them to develop. Without the ability to focus intensely and follow an idea wherever it leads, the world could miss out on breakthroughs that come from putting your mind to something and keeping it there, even when the dopamine hit of a quick distraction is one click away.

Another alarming finding in the book is the significant gender divide at play here. Severe mental health challenges seem to have hit young women especially hard in recent years. Meanwhile, young men’s academic performance is worsening, their college attendance is dropping, and they’re failing to develop the social skills and resilience that come from real-world interaction and risk-taking. In other words: Girls are falling into despair while boys are falling behind.

The solutions Haidt proposes aren’t simple, but I think they’re needed. He makes a strong case for better age verification on social media platforms and delaying smartphone access until kids are older. Literally and figuratively, he argues, we also need to rebuild the infrastructure of childhood itself—from creating more engaging playgrounds that encourage reasonable risk-taking, to establishing phone-free zones in schools, to helping young people rediscover the joy of in-person interaction. Achieving this won’t come from individual families making better choices; it requires coordination between parents, schools, tech companies, and policymakers. It also demands more research into the effects of these technologies, and the political will to act on what we learn.

The Anxious Generation is a must-read for anyone raising, working with, or teaching young people today. With this book, Haidt has given the world a wake-up call about where we’re headed—and a roadmap for how we can change course.

Starting line

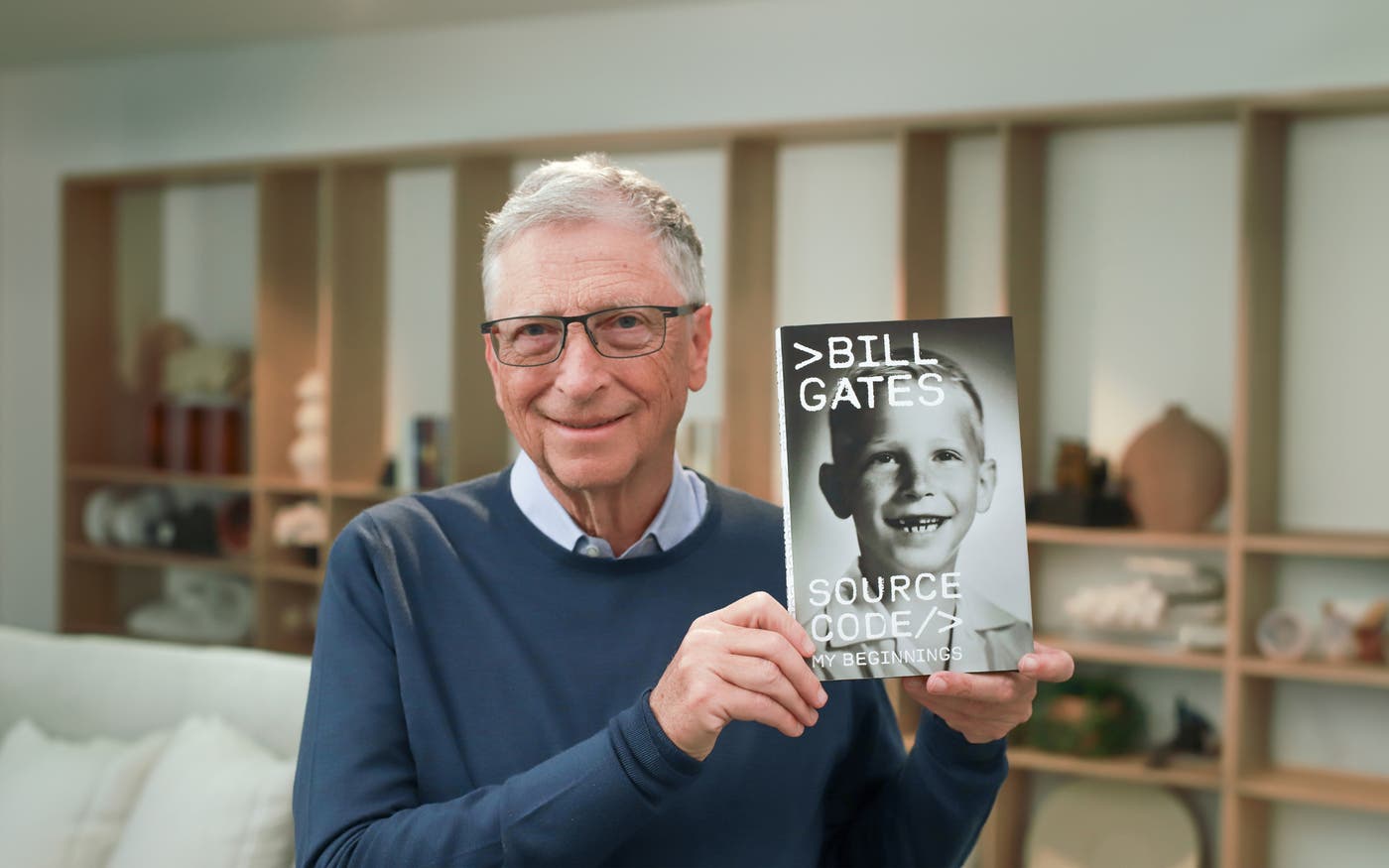

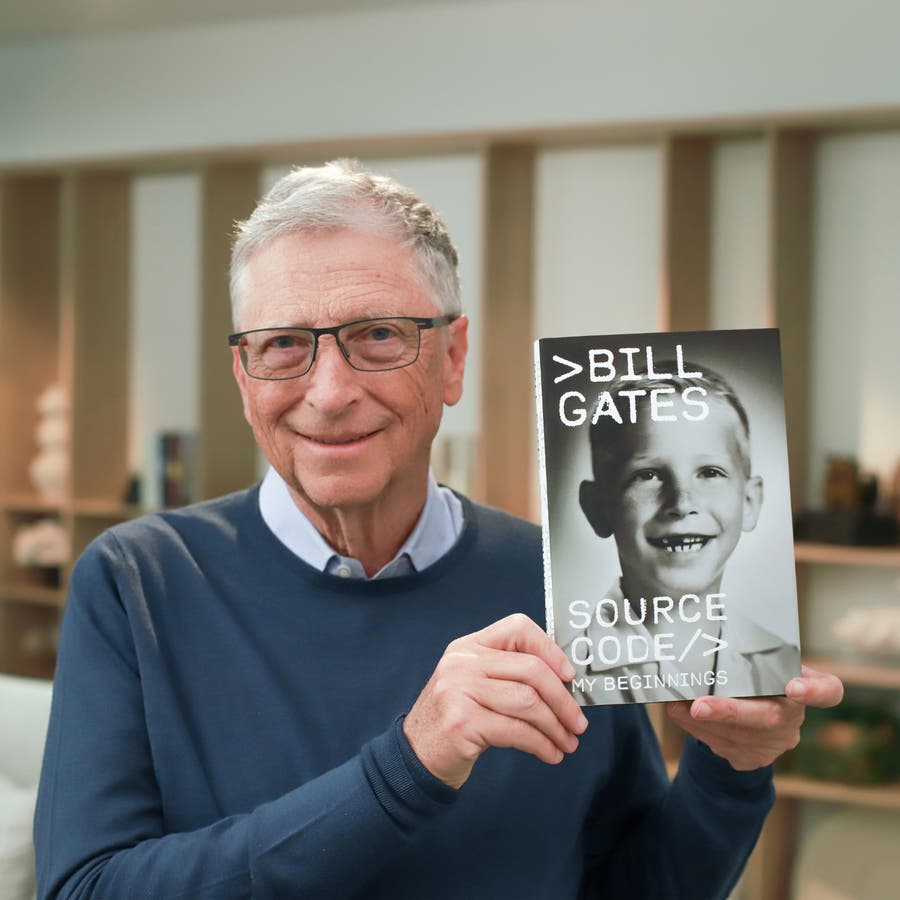

My first memoir is now available

Source Code runs from my childhood through the early days of Microsoft.

I was twenty when I gave my first public speech. It was 1976, Microsoft was almost a year old, and I was explaining software to a room of a few hundred computer hobbyists. My main memory of that time at the podium was how nervous I felt. In the half century since, I’ve spoken to many thousands of people and gotten very comfortable delivering thoughts on any number of topics, from software to work being done in global health, climate change, and the other issues I regularly write about here on Gates Notes.

One thing that isn’t on that list: myself. In the fifty years I’ve been in the public eye, I’ve rarely spoken or written about my own story or revealed details of my personal life. That wasn’t just out of a preference for privacy. By nature, I tend to focus outward. My attention is drawn to new ideas and people that help solve the problems I’m working on. And though I love learning history, I never spent much time looking at my own.

But like many people my age—I’ll turn 70 this year—several years ago I started a period of reflection. My three children were well along their own paths in life. I’d witnessed the slow decline and death of my father from Alzheimer’s. I began digging through old photographs, family papers, and boxes of memorabilia, such as school reports my mother had saved, as well as printouts of computer code I hadn't seen in decades. I also started sitting down to record my memories and got help gathering stories from family members and old friends. It was the first time I made a concerted effort to try to see how all the memories from long ago might give insight into who I am now.

The result of that process is a book that will be published on Feb. 4: my first memoir, Source Code. You can order it here. (I’m donating my proceeds from the book to the United Way.)

Source Code is the story of the early part of my life, from growing up in Seattle through the beginnings of Microsoft. I share what it was like to be a precocious, sometimes difficult kid, the restless middle child of two dedicated and ambitious parents who didn’t always know what to make of me. In writing the book I came to better understand the people that shaped me and the experiences that led to the creation of a world-changing company.

In Source Code you’ll learn about how Paul Allen and I came to realize that software was going to change the world, and the moment in December 1974 when he burst into my college dorm room with the issue of Popular Electronics that would inspire us to drop everything and start our company. You’ll also meet my extended family, like the grandmother who taught me how to play cards and, along the way, how to think. You’ll meet teachers, mentors, and friends who challenged me and helped propel me in ways I didn’t fully appreciate until much later.

Some of the moments that I write about, like that Popular Electronics story, are ones I’ve always known were important in my life. But with many of the most personal moments, I only saw how important they were when I considered them from my perspective now, decades later. Writing helped me see the connection between my early interests and idiosyncrasies and the work I would do at Microsoft and even the Gates Foundation.

Some of the stories in the book were hard for me to tell. I was a kid who was out of step with most of my peers, happier reading on my own than doing almost anything else. I was tough on my parents from a very early age. I wanted autonomy and resisted my mother’s efforts to control me. A therapist back then helped me see that I would be independent soon enough and should end the battle that I was waging at home. Part of growing up was understanding certain aspects of myself and learning to handle them better. It’s an ongoing process.

One of the most difficult parts of writing Source Code was revisiting the death of my first close friend when I was 16. He was brilliant, mature beyond his years, and, unlike most people in my life at the time, he understood me. It was my first experience with death up close, and I’m grateful I got to spend time processing the memories of that tragedy.

The need to look into myself to write Source Code was a new experience for me. The deeper I got, the more I enjoyed parsing my past. I’ll continue this journey and plan to cover my software career in a future book, and eventually I’ll write one about my philanthropic work. As a first step, though, I hope you enjoy Source Code.

Not-so-small talk

A good read for great connections

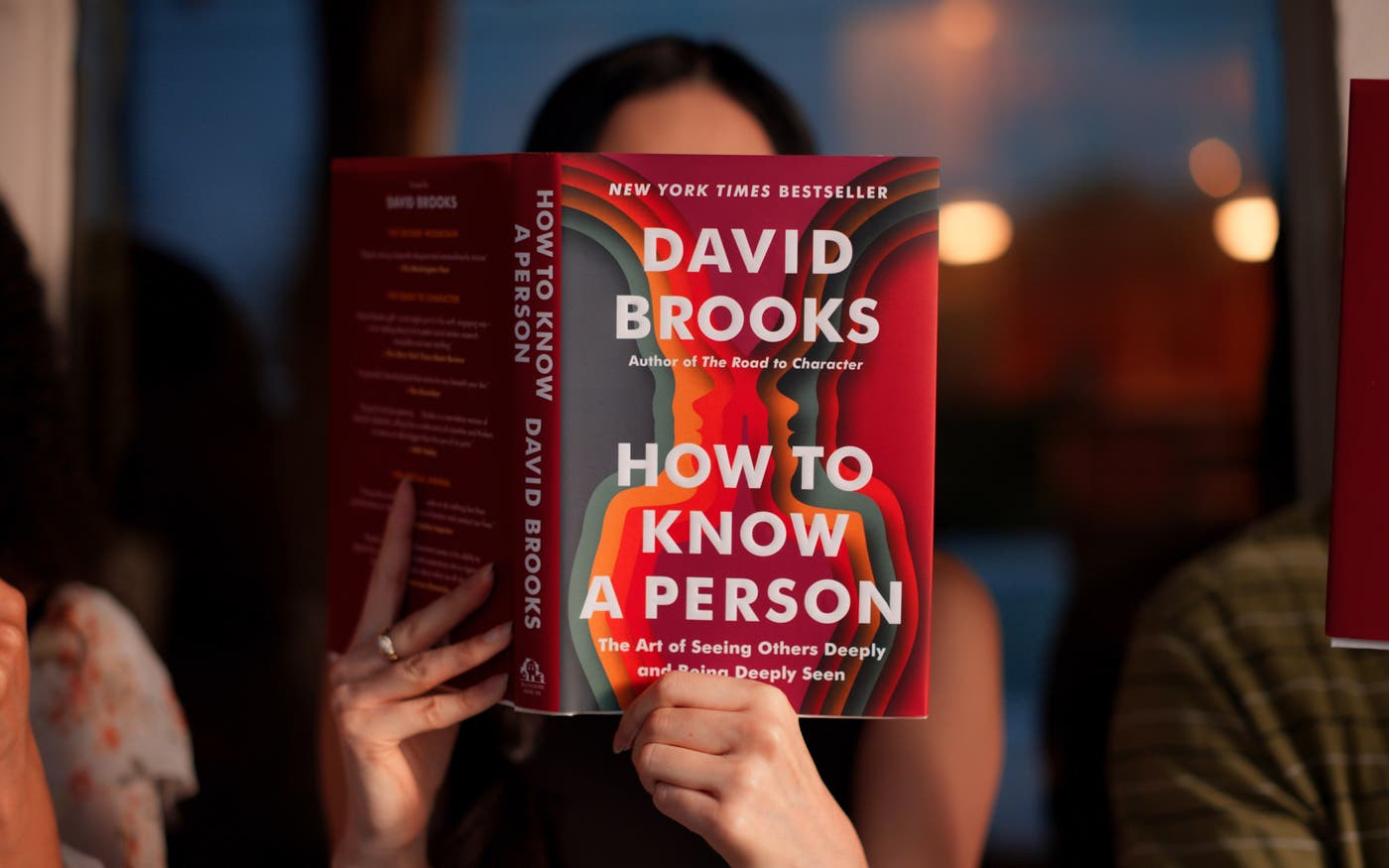

David Brooks’ new book teaches us how—and why—to make every word count.

When I was younger, I would have been perfectly happy spending hours alone in my room reading, learning about my latest obsession, and letting my mind wander. But my mom was intentional about creating opportunities for me to engage and socialize—encouraging me to interact with all the guests who visited our house and making me serve as a greeter at my dad’s work events. She believed that connecting with others was a skill that had to be cultivated, even (or perhaps especially) for an introverted kid like me.

I’ve been thinking about that a lot lately after reading David Brooks's newest book, How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen. It was recommended to me by my friend Bernie Noe, and I was eager to dive in because I know David and enjoyed his previous book, The Road to Character. (Also: Whenever Bernie recommends a book to me, I read it.) The key premise is one I haven't found in any other book: that conversational and social skills aren't just innate traits—they can be learned and improved upon.

As someone who has always been more comfortable making software than small talk, I found this idea both refreshing and informative. As a result, even though some of its advice may seem fairly rudimentary, the book is now my favorite of anything David has written.

While reading How to Know a Person, I took a ton of notes and reflected on my own communication style. In Chapter 6, "Good Talks," David dives into what makes a conversation meaningful. It really got me thinking about when I am fully present and engaged in a conversation, and when am I just trying to preserve my energy or avoid being interrupted. I had to laugh at myself a bit, because I know I've been guilty of talking about topics I find fascinating, like the history of fertilizer, without always checking to see if the other person is interested.

One powerful takeaway from the book is the importance of active listening—or, as David calls it, loud listening. “When another person is talking,” he writes, “you want to be listening so actively that you’re practically burning calories.” I’m pretty good at that kind of listening when I’m super interested in a topic, especially when I’m learning something new. But the book made clear how transformative it can be to bring that same enthusiasm when listening to someone talk about a hardship they’re dealing with or an accomplishment they’re proud of.

Fortunately, the book is full of practical advice for doing that. David emphasizes something I’ve found really helpful in my own life: asking open-ended questions—with phrases like "How did you…," "What's it like…," "Tell me about…," and "In what ways…"—that invite people to share their experiences and perspectives in a more in-depth way. David also recommends using the "looping" technique, where you paraphrase what someone has just said to ensure you've understood them correctly. And he endorses what experts call the SLANT method to convey attention and interest in a conversation: Sit up, Lean forward, Ask questions, Nod, and Track the speaker.

What I found especially compelling about the book is how it shows that these skills are relevant across all kinds of relationships and interactions. Whether you're catching up with a close friend, chatting with a coworker, or just exchanging pleasantries with someone while waiting in line for a cheeseburger, being fully present and attuned can transform the encounter. These simple practices can go a long way in making others feel heard and valued.

The more I read, the more I realized how much the book's insights connect to the broader challenges we face in today's world. Back in 1995, when I wrote The Road Ahead, I predicted that technology would make it easier for us to stay connected with our hometowns and share our lives with others. And in many ways, it has. But David argues in Chapter 8, "The Epidemic of Blindness," that technology has also contributed to a growing sense of loneliness and disconnection. We may be more connected than ever, but are we truly seeing and understanding each other?

This question becomes even more urgent when considering the social and political divisions David highlights. The statistics he cites about the rise in depression, suicide, and distrust are alarming, and he makes the case that this social unraveling is fueling our political divides. His discussion about how politics can become a substitute for genuine connection—leading people to get their satisfaction from yelling at those they disagree with instead of trying to understand them—highlights a trend that worries me a great deal.

In the book, David connects these social ills to changes in our education system. He argues that schools have shifted away from teaching what he calls “moral and social skills,” and that this has left us ill-equipped to build strong relationships and communities. It’s an interesting and timely argument for sure, but I wished it were further built out. I’d be interested in reading more about how David defines this type of teaching, how he measures the changes, and how he thinks education can help reverse some of these troubling social trends. In fact, I think there’s another book waiting to be written here.

For the most part, though, what makes David's book so compelling is that it challenges us to put its insights into practice. It's about being intentional in our interactions, whether that means asking more thoughtful questions, fully listening to the answers, or expressing genuine appreciation. It's about approaching conversations with generosity and curiosity, looking for ways to connect and understand. And it's about realizing that even small things—like asking the right question at the right time or giving a nice compliment—can make a big difference in building relationships. I’m certain that what I learned from the book will stay with me for a long time.

Overall, I can’t recommend How to Know a Person highly enough. More than a guide to better conversations, it’s a blueprint for a more connected and humane way of living. It's a must-read for anyone looking to deepen their relationships and broaden their perspectives—and I believe it has the power to make us better friends, colleagues, and citizens.

Give it up

The head of TED has his own ideas worth spreading

Infectious Generosity is a timely, inspiring read about philanthropy in the digital age.

If you don’t know Chris Anderson’s name, you probably know his work. As the curator of TED for over two decades, Chris has transformed the once-exclusive conference into a global platform for ideas that “change everything”—making TED Talks a household name in the process. Chris and I share a deep interest in how innovation can help tackle major challenges and improve the world. We've collaborated several times, and he’s invited me to the TED stage periodically since 2009.

So when Chris told me about his new book, Infectious Generosity—which explores how the internet can amplify the impact of generosity—I was excited to dive in.

Chris’s central argument is that communications technology creates both an opportunity and a responsibility to give more. When we can witness the hardships of others firsthand, even from the other side of the planet, our instinct to help is activated. And the internet makes it easy to act on that instinct.

The book is filled with powerful examples of this dynamic in action, including viral fundraising campaigns like the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge, which raised over $200 million to fight the disease (and which I participated in), and online platforms like DonorsChoose, which allows anyone to support a classroom project with just a few clicks. Each story shows the power of people joining up to do extraordinary things.

But Chris doesn't gloss over the challenges of the digital age. Like other observers, he notes that social media platforms have turned the internet into an “outrage-generating machine” that drives us apart instead of bringing us together. As we saw with the spread of Covid-19 misinformation, online spaces can easily promote polarization and falsehoods instead of empathy and truth. What’s more—even as the ease of giving has increased, overall giving levels have not. In fact, a 2022 report from Giving USA found that individual giving as a percentage of disposable income has remained relatively flat over the past four decades.

People are more connected than ever—but that connection hasn’t always fostered the generosity we’d want and expect. That will only happen at scale, Chris argues, if individuals, nonprofits, businesses, and policymakers all make a concerted effort. Fortunately, the book offers a roadmap we can follow: Tell more uplifting stories of everyday generosity, redesign social media to promote prosocial behavior, and expand our definition of generosity itself—to include bridging divides, sharing knowledge, enabling connections, extending hospitality, and others.

I was especially intrigued by Chris's proposal of a “universal giving pledge,” where everyone commits to donating 10 percent of their income or 2.5 percent of their wealth annually. It’s similar to what many religions already encourage of their followers, if only by another name. And it’s reminiscent of the Giving Pledge, which Melinda, Warren Buffett, and I launched in 2010 to encourage billionaires to dedicate the majority of their wealth to philanthropy, either in their lifetime or wills. For me, that has meant working to save and improve lives through the Gates Foundation—which is the most meaningful work of my life.

Just as the Giving Pledge aims to make giving the norm among the wealthy, a universal pledge has the potential to inspire millions of people at all income levels to give more. If universally adopted, Chris calculates, such a pledge would generate over $10 trillion every year and unlock immense new resources to address health, poverty, education, and more.

Reading this book, I was reminded of my own mindset when I first thought about the digital revolution—about how it could bring the world closer together, make people feel less lonely, and help us tackle our biggest challenges. It’s great to see that someone still passionately believes in that promise and has ideas for how we can make good on it.

It's true that a few of Chris’s boldest, most ambitious proposals, like the universal giving pledge, will be challenging to implement. Still, I find his idealism infectious and inspired—especially because advances in artificial intelligence will likely amplify technology's potential as a generosity engine. At a minimum, AI will give us more potent tools to understand causes, mobilize donors, and target giving for maximum impact in the coming years. The key is to design these systems so they identify inequities, catch our biases, tap into the best of human nature, and nudge us toward our most generous selves.

If you want to help create a more generous world but don’t know where to start, Infectious Generosity is the book for you. It's an invitation to rethink and reinvent philanthropy for the digital age—and I believe that if enough of us embraced its message, the world really would be a much more generous place.

Smil test

Is this really an unrivaled era of innovation?

Vaclav Smil has written “a brief history of hype and failure.”

There is one writer whose books I’ve reviewed on Gates Notes more than anyone else: Vaclav Smil. I’ve read all of his 44 books, which cover everything from the role of energy in human life to changes in the Japanese diet. I find his perspective to be super valuable. Although sometimes he’s too pessimistic about the upside of new technologies, he’s almost always right—and informative—when it comes to the complexities of deploying those technologies in the real world.

In his newest book, Invention and Innovation: A Brief History of Hype and Failure, Smil looks skeptically at the notion that we’re living in an unrivaled era of innovation. Based on his analysis of fields including agriculture, transportation, and pharmaceuticals, he concludes that our current era is not nearly as innovative as we think. In fact, he says, it shows “unmistakable signs of technical stagnation and slowing advances.”

This conclusion feels especially counterintuitive at a time when artificial intelligence and deep learning are advancing so fast. But to Smil, AI researchers only have managed “to deploy some fairly rudimentary analytical techniques to uncover patterns and pathways that are not so readily discernible by our senses” and produced “impressive achievements on some relatively easy tasks.”

Smil believes there was only one real period of explosive innovation in the past 150 years: 1867-1914. During those years, inventors created internal combustion engines, electric lights, the telephone, inexpensive methods of producing steel, aluminum smelting, plastics, and the first electronic devices. Humanity also gained revolutionary insights in the fields of infectious disease, medicine, agriculture, and nutrition.

Smil argues that the ensuing years have been lackluster, with far more “breakthroughs that are not” than important inventions that achieve scale and stick in the marketplace. One of his iconic examples of a false breakthrough is leaded gasoline, which helped internal combustion engines operate much more smoothly but produced devastating cognitive declines and millions of premature deaths.

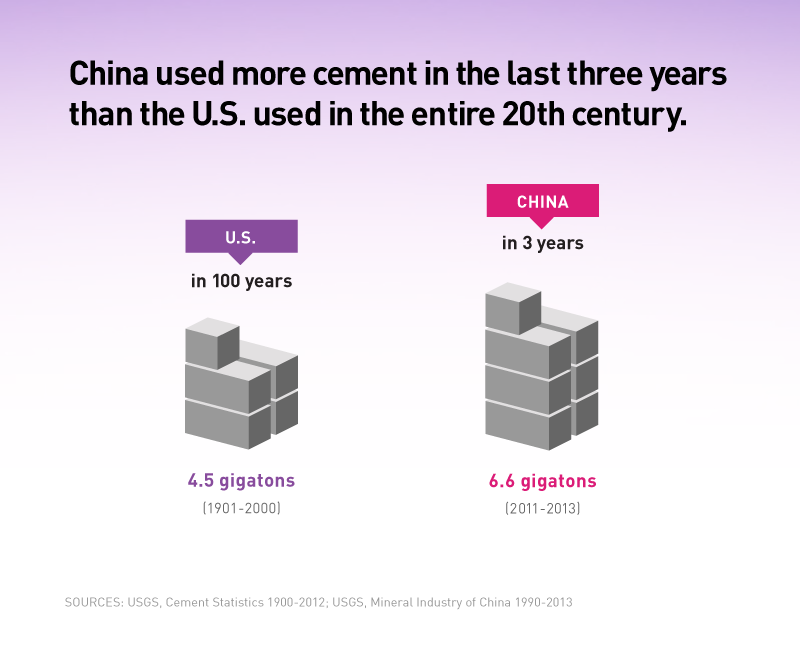

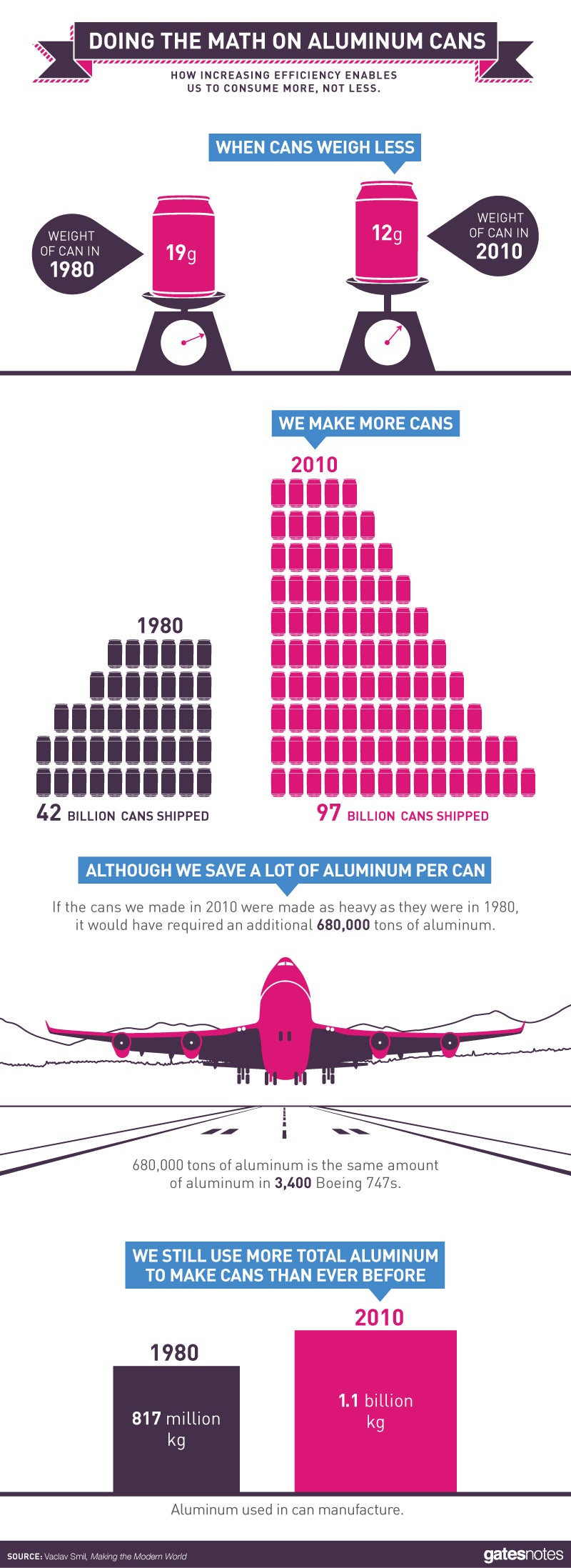

One thing that I agree with him about is how the exponential growth in computing power over the past several decades has given people a false idea about growth and innovation in other areas. Smil acknowledges “the much-admired post-1970 ascent of electronic architecture and performance,” but he concludes that this growth “has no counterpart in … other aspects of our lives.” It’s misguided to assume that anything else will grow as fast as computing power has.

On the other hand, I think Smil underestimates accomplishments in AI. The past two years of AI improvement, particularly large language models, have surprised all of us. In fact, we’re starting to see early signs that machines can produce human-like reasoning—moving beyond just producing answers to questions they were programmed to solve. AI is going to become smart, not just fast. When it achieves what researchers call “artificial general intelligence,” that will give humanity incredible new tools for problem solving in almost every domain, from curing disease to personalizing education to developing new sources of clean energy. And as I wrote earlier this year, we will have to develop strict guidelines and protocols to curtail negative outcomes.

Smil also neglects to account for the convergence of new technologies. In the work I do with the Gates Foundation and Breakthrough Energy, I have a great vantage point for observing innovation driven not just by advances in one area (AI, for example) but by the compounding effects of many different technologies advancing at the same time, like digital simulations, storage capacity, mobile communications, and domain-specific tools such as gene sequencing.

Smil is also pessimistic about many green technologies, including some approaches that I’m investing in. For example, he describes sodium-cooled nuclear fission reactors as pie in the sky. And yet in May I walked on the ground that will soon be broken for just such a reactor. Thanks to advances in digital simulation as well as ample risk capital, TerraPower has designed a sodium-cooled reactor that could be delivering power to the grid by 2030. Even if it takes longer to get running, I’m optimistic that sodium-cooled reactors are not just technically possible but will also prove to be economically viable, safe, and helpful for achieving net-zero carbon emissions.

Every Smil book that I own is marked up with lots of notes that I take while reading. Invention and Innovation is no exception. Even when I disagree with him, I learn a lot from him. Smil is not the sunniest person I know, but he always strengthens my thinking.

Inner Game of Tennis

The best guide to getting out of your own way

A profound book about tennis and much more.

When Roger Federer announced his retirement, I thought of a fascinating insight he once gave me into his playing style. One of the keys to his success, he told me, is his incredible ability to keep his cool and remain calm.

Anyone who saw Roger play knows what he meant. When he got down, he knew he might need to push himself a little more, but he never worried too much or got too down on himself. And when he won a point, he didn’t waste a lot of energy congratulating himself. His style was the opposite of someone like John McEnroe, who showed all of his emotions and then some.

I was glad to hear Roger talk about that element of his game, because it’s something I’ve been trying to incorporate in my own way since the mid-70s, when I first came across Timothy Gallwey’s groundbreaking book The Inner Game of Tennis. It’s the best book on tennis that I have ever read, and its profound advice applies to many other parts of life. I still give it to friends today.

Inner Game was published in 1974 and was a big hit. Gallwey, a successful tennis coach based in southern California, introduced the idea that tennis is composed of two distinct games. There’s the outer game, which is the mechanical part—how you hold the racket, how you keep your arm level on your backhand, and so on. It’s the part that most coaches and players tend to focus on.

Gallwey acknowledged the importance of the outer game, but what he was really interested in, and what he thought was missing from most people’s approach, was the inner game. “This is the game that takes place in the mind of the player,” he wrote. Unlike the outer game, where your opponent is the person on the other side of the net, the inner game “is played against such obstacles as lapses in concentration, nervousness, self-doubt, and self-condemnation. In short, it is played to overcome all habits of mind which inhibit excellence in performance.”

That idea resonated with me so well that I read the book several times, which is unusual for me. Before I read it, in just about every match I would say to myself at some point: "I’m so mad that I missed that shot. I’m so bad at this." That negative reinforcement would linger, so during the next point, I was still thinking about that bad shot. Gallwey presented ways of letting go of those negative feelings and getting out of your own way so you could move on to the next point.

Gallwey had one particular insight that seems crazy the first time you hear it. “The secret to winning any game,” he wrote, “lies in not trying too hard.”

How could you expect to win by not trying too hard? “When a tennis player is ‘in the zone,’ he’s not thinking about how, when, or even where to hit the ball,” Gallwey wrote. “He’s not trying to hit the ball, and after the shot he doesn’t think about how badly or how well he made contact. The ball seems to get hit through a process which doesn’t require thought.” (Gallwey was writing at a time when it was still common to use the word “he” to refer to everyone.)

The inner game is really about your state of mind. Is it helping you or hurting you? For most of us, it’s too easy to slip into self-criticism, which then inhibits our performance even more. We need to learn from our mistakes without obsessing over them.

Gallwey and his readers quickly realized that the inner game wasn’t just about tennis. He went on to publish similar books about golf, skiing, music, and even the workplace: He created a consulting business that caters to Fortune 500 companies.

Even though I stopped playing tennis in my 20s so I could focus on Microsoft and didn’t start again until my forties, Gallwey’s insights subtly affected how I showed up at work. For example, although I’m a big believer in being critical of myself and objective about my own performance, I try to do it the Gallwey way: in a constructive fashion that hopefully improves my performance.

And although I’m not always perfect at it, I try to manage teams the same way. For example, years ago, there was an incident where a team at Microsoft discovered a bug in a piece of software they had already shipped to stores. (This was back when software was sold on discs.) They would have to recall the software, at significant cost to the company. When they told me the bad news, they were really beating themselves up. I told them, “I’m glad you’re admitting that you need to replace the discs. Today you lost a lot of money. Tomorrow, come in and try to do better. And let’s figure out what allowed that bug to make it into the product so it doesn’t happen again.”

Tennis has evolved over the years. The best players in the world today play a very different style from the champions of 50 years ago. But The Inner Game of Tennis is just as relevant today as it was in 1974. Even as the outer game has changed, the inner game has remained the same.

Facts of life

What sweat, wine, and electricity can teach us about humanity

Numbers Don’t Lie is Vaclav Smil’s most accessible book yet.

Vaclav Smil is my favorite author, but I sometimes hesitate to recommend his books to other people. His writing, while brilliant, is often too detailed or obscure for a general audience. (Deep dives on Japanese dining habits or natural gas can be a tough sell for even the smartest, most thoughtful readers.) Still, I’m a big enough fan to keep telling my friends and colleagues about his books, even though I know most of them won’t take me up on my recommendations.

That’s why I was thrilled when Vaclav released his most accessible book yet. Numbers Don’t Lie: 71 Things You Need to Know About the World, which came out last fall, takes everything that makes his writing great and boils it down into an easy-to-read format. I unabashedly recommend this book to anyone who loves learning.

This is probably the most information Vaclav has ever put in a book, and yet it’s by far the most digestible. Each chapter is just a couple pages long and covers one of the 71 facts mentioned in the title. Here are three that I found particularly interesting:

1.

You can thank sweat glands for our big brains.

Humans are the grand champions of sweating. We’re able to remove heat from our bodies through perspiration better than any other mammal (partly because we have very little hair). Vaclav writes, “In the race of life, we humans are neither the fastest nor the more efficient. But thanks to our sweating capabilities, we are certainly the most persistent.”

Our ancestors had better endurance than the animals they hunted for food, which allowed them to run down rich sources of protein that provided the fuel for our brains to develop. The next time you feel miserable on a hot day, just think about how all the sweating you’re doing is the reason you’re so smart!

2.

The French are drinking a lot less wine than they used to.

“Viticulture, wine-drinking, and wine exports have been long established as one of the key signifiers of national identity” in France, writes Vaclav. In 1926, the average French person drank an impressive 136 liters of wine (or more than 35 gallons). But by 2020, that figure had shrunk to just 40 liters.

The idea that French wine consumption is now a third of what it was a century ago is amazing to me because of what it might reveal about how society is changing. While young French people are drinking less alcohol overall, the consumption of mineral and spring water has doubled since 1990. Does that mean the French are becoming more health conscious? Was life just so bleak in the 1920s that people had to drink? Have people replaced drinking wine with other diversions like watching TV or browsing the web? I love how this book forces you to think about the story behind a seemingly niche statistic.

3.

The 1880s might be the most consequential decade in human history.

One of my favorite things about Vaclav’s writing is his ability to put history in context. Although it’s tempting to see the era we’re living in now as a time of unprecedented innovation, he argues that the 1880s saw the real technology boom. The decade saw the discovery of electricity and the internal combustion engine—along with somewhat less consequential but still important innovations like the ballpoint pen, the modern bicycle, and Coca-Cola. If you want to read more about the inventions the 1880s gave us, you can download a free chapter here:

Vaclav believes that progress comes in fits and starts rather than in a constant stream. Humanity will go through long periods where everything stays the same, and then a new invention will come along that sets off a rapid period of change. For example, Thomas Edison’s discovery enabled the creation of the electric elevator in 1889. This, in turn, let us build taller buildings like skyscrapers since people would no longer have to rely on stairs to reach the top floor. City skylines would look a lot different today if it weren’t for the 1880s.

If you read Numbers Don’t Lie and like it, you might also enjoy Vaclav’s latest book Grand Transitions. Numbers Don’t Lie(He is nothing if not prolific, having released two books during the pandemic.) It looks at how societies are shaped by shifts in demographics, agriculture, economics, and energy use. It’s not quite as accessible as , but the subject matter is so interesting that I think people will find it worthwhile.

Vaclav finds as much joy and fascination in looking to the past as anyone else I know. As someone who tends to be optimistic about technology—maybe even too optimistic at times—I appreciate how his natural skepticism about future innovation keeps my outlook realistic. If you’re looking for someone to help you understand how history ties together, you can’t do better than Vaclav—and Numbers Don’t Lie is a great place to start.

Too big to succeed

What happened to GE?

The fall of one of America’s great companies.

GE is a mythic corporation. It was at one time the largest, most powerful company in the world. Its founding story includes the innovator Thomas Edison and financier J.P. Morgan. Its legendary CEO Jack Welch, who wrote five bestselling books on leadership, became a model for an entire generation of executives. When GE started using Microsoft software in our early days, that gave us a huge boost in the market, because GE was such a bellwether company.

It turns out that the word “mythic” is the perfect word for GE. The corporation has come crashing to Earth in one of the greatest downfalls in business history. Its workforce has been hollowed out, from 333,000 employees in 2017 to fewer than 174,000 at the end of last year. Its share price has fallen precipitously. In 2018, GE was dropped from the Dow Jones Industrial Average after more than a century in the index.

GE’s fall is not the result of innovators developing a better jet engine or wind turbine. It’s also not a case of outright fraud, like Enron. It’s a textbook case of mismanagement of an overly complex business.

Only a few people saw it coming (including one, ironically, from J.P. Morgan’s namesake bank). I wish I could tell you that I was one of them, but I was just as surprised as most people.

That’s why I was eager to read Lights Out: Pride, Delusion, and the Fall of General Electric, by the Wall Street Journal reporters Thomas Gryta and Ted Mann. I wanted to understand what really went wrong and what lessons this story holds for investors, regulators, business leaders, and business students.

At times, it was a bit hard for me, as a former CEO, to read such harsh criticism of fellow leaders, including people I know and like. But I got a lot out of reading this book. Gryta and Mann gave me the detailed insight I was looking for into the culture, decisions, and accounting that eventually caught up to GE in a gigantic way.

My first big takeaway is that one of GE’s greatest apparent strengths was actually one of its greatest weaknesses. For many years, investors loved GE’s stock because the GE management team always “made their numbers”—that is, the company produced earnings per share at least as large as what Wall Street analysts predicted. It turns out that culture of making the numbers at all costs gave rise to “success theater” and “chasing earnings.” In Gryta and Mann’s words, “Problems [were] hidden for the sake of preserving performance, thus allowing small problems to become big problems before they were detected.”

Chapter 14 of Lights Out details many of the gimmicks GE employed to make the numbers look better than they really were. For example, Gryta and Mann report that GE would sometimes artificially boost quarterly profits by selling an asset (e.g., a diesel train) to a friendly bank, knowing that it could then buy back the asset at a time of GE’s choosing.

There are a lot of ways a company can end up with a culture that rewards gaming the numbers. Although Steve Ballmer and I made our share of strategic mistakes, we were maniacal about making sure our numbers were rock solid and avoiding incentive systems where people could cram a lot of sales into a quarter in order to look good or meet some quota. Satya Nadella works the same way today.

In many companies, bad news travels very slowly, while good news travels fast. We tried hard to combat that. A team member might send me mail saying “we just won a software design competition,” and “isn’t this amazing?” I’d typically respond, “Why am I hearing about this one? That’s not statistically representative. How many competitions did we lose?” I used the term “making bad news travel fast” all the time. I wanted to catch negative trends early, when we could still do something about them.

My second big takeaway from Lights Out is that GE didn’t have the right talent and systems to bundle together a dizzying array of unrelated businesses—including moviemaking, insurance, plastics, and nuclear power plants—and manage them well. Investors bought into the notion that the company’s world-renowned training made it better at managing things than anyone else, and that GE could produce consistent profits even in highly cyclical markets. And GE successfully persuaded people that its generalists could avoid the pitfalls that had tripped up big conglomerates in the past.

In reality, those generalists often didn’t understand the specifics of the industries they had to manage and couldn’t navigate trends in their industries. For example, the authors make the case that CEO Jeff Immelt didn’t have a good handle on its huge banking unit, GE Capital. “Making money from [GE Capital] seemed shockingly simple to him at first, as it had to Welch, but the balance sheets were treacherously complex, and deep risks lurked there and were not always easily spotted in the quarterly profits and losses,” write Gryta and Mann. One former GE executive told the authors that “Immelt struggled with basic concepts—the difference between secured and unsecured debt, for instance, which was fundamental to a lending operation like GE Capital.”

This dynamic was not confined to Immelt. It was rampant throughout the company’s top ranks. As a result, the ability of top executives to understand what was really going on was quite limited. The only people who could actually dig down into the numbers and see what was going on were in finance. And as I mentioned above, the finance people didn’t have much incentive to bring negative news to Welch or Immelt.

In my role at our foundation, I sometimes hear fellow philanthropists say things like, “I just wish my grantees could operate more like a business.” The story of GE, led by very smart men who cared deeply about their work, should tamp down that kind of talk. The truth is that businesses, even the giants of industry, are just as susceptible to mistakes as any nonprofit. Anyone who wants to avoid the mistakes made by GE should read this book.

In general

We need more Rogers

David Epstein’s Range explains the greatness of Roger Federer and other generalists.

Just before COVID-19 hit, I was paired with Roger Federer in a tournament to benefit children’s education in Africa. When I watch Roger play, I’m in awe. As the late novelist David Foster Wallace wrote, he is “one of those rare, preternatural athletes who appear to be exempt, at least in part, from certain physical laws.”

Here’s the surprising part about Roger’s greatness: As a young kid, he didn’t focus on tennis and didn’t get fancy coaching or strength training. He played a wide range of different sports, including skateboarding, swimming, ping pong, soccer, and badminton. He didn’t start playing competitive tennis until he was a teenager. Even then, his parents discouraged him from taking it too seriously.

I learned this from reading a good, myth-debunking book called Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World. The sports journalist David Epstein uses Roger’s experience as his opening example of the underappreciated benefits of delaying specialization and accumulating a breadth of different experiences. “In a world that increasingly incentivizes, even demands, hyperspecialization,” he writes, “we … need more Rogers: people who start broad and embrace diverse experiences and perspectives while they progress.”

Epstein, whom I learned about from his fantastic 2014 TED talk on sports performance, acknowledges that there are certain pursuits, like golf and classical music, where it does make sense to go all in as early as possible. But these are outliers, because they’re rooted in repetitive patterns and clearly defined solutions. “The world is not golf, and most of it isn’t even tennis,” Epstein writes. Instead, the world is like a game where “you can see the players on the court with balls and rackets, but nobody has shared the rules. It is up to you to derive them, and they are subject to change without notice.”

My own career fits the generalist model pretty well. As a kid, I used to sneak out of my basement bedroom to do late-night coding at the University of Washington, but my passion for computers was always mixed with many other interests. I spent a lot of time reading books on a wide range of topics.

I believe that one of the key reasons Microsoft took off is because we thought more broadly than other startups of that era. We hired not just brilliant coders but people who had real breadth within their field and across domains. I discovered that these team members were the most curious and had the deepest mental models.

Epstein provides a good framework for understanding why polymaths are so important for innovation. “In kind environments, where the goal is to re-create prior performance with as little deviation as possible, teams of specialists work superbly.” That’s why if I had to get surgery, I’d seek out a subspecialist who had a lot of experience with whatever procedure I needed. But when it’s a “wicked environment,” your job is not to repeat a complex procedure. By definition, it’s to do something that no one has done before. Epstein reports that when researchers study great innovators, they find “systems thinkers” with an “ability to connect disparate pieces of information from many different sources” and who “read more (and more broadly) than other technologists.” Theatrical innovator Lin-Manuel Miranda calls this having “a lot of apps open” in one’s brain at the same time. I like that image.

Epstein finds that there’s another good reason to encourage range: “In a wicked world, relying upon expertise from a single domain … can be disastrous.” Chapter 10 (“Fooled by Expertise”) is dedicated to showing how hyperspecialists are susceptible to tunnel vision. For example, he cites a study of 284 top experts on Soviet and Russian affairs. This 20-year study found that, on average, the so-called experts “were bad at short-term forecasting, bad at long-term forecasting, and bad at forecasting in every domain…. [They were] roughly as accurate as a dart-throwing chimpanzee.” But there was one subgroup that turned out to be much more accurate. These were experts “who were not vested in a single approach,” “chose to look at new evidence, whether or not it agreed with their current beliefs,” and “were much more likely to adjust their ideas … when an outcome took them by surprise.”

Epstein offers up Charles Darwin as the ultimate example of someone whose breadth made it possible for him to remain open-minded and innovative. Before Darwin got aboard the HMS Beagle and sailed to the Galapagos, he had trained not only in natural history but also medicine, theology, philosophy, and geology. This cross-training helped him build the intellectual muscles he would need to overturn centuries of dogma. “He made a point of copying into his notes any fact or observation he encountered that ran contrary to a theory he was working on,” Epstein writes. “He relentlessly attacked his own ideas, dispensing with one model after another, until he arrived at a theory that fit the totality of the evidence.”

My only criticism of Range is that you could come away with the impression that Epstein, a generalist himself, is too critical of specialists. If you’re enthusiastic about a hyperspecialized field like molecular biology or quantum physics, go for it. Just give yourself some room to explore what your friends and colleagues in other fields are learning.

Behind bars

An eye-opening look into America’s criminal justice system

The New Jim Crow will help you understand the history and the numbers behind mass incarceration.

My last holiday books list included a novel called An American Marriage which really stuck with me over the previous year. I was deeply touched by its story of a husband torn away from his wife by a false accusation that lands him in prison. The book did a beautiful job of showing how incarceration can devastate a family, even after release from prison.

As moving as the book was, the story was fiction. But the idea of a family torn apart by mass incarceration is not. If you’re interested in learning more about the real lives caught up in our country's justice system, I highly recommend The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander. It offers an eye-opening look into how the criminal justice system unfairly targets communities of color—and especially Black communities.

The book was released more than 10 years ago, but this is a topic that has taken on extra relevance this year. The horrifying killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor set off a summer of protests that put Black Lives Matter front and center. Like many white people, I’ve committed to reading more about and deepening my understanding of systemic racism. Alexander’s book is about much more than the police—whom she describes as the “point of entry” into the justice system—but it provides useful context to understand how we got to where we are.

Alexander explains how mass incarceration is a cycle. Once you’ve been in prison, you can’t often get a job after you get out because having a felony on your record makes it hard to get hired. In some cases, the only way to make money and support your family is through illicit means—which can land you back in prison. The result of this cycle is a permanent underclass that is disproportionately Black and low-income. (Alexander also talks about this in Ava DuVernay’s excellent documentary 13th.)

The book is good at explaining the history and the numbers behind mass incarceration. I was familiar with some of the data, but Alexander really helps put the numbers—especially around sentencing and the War on Drugs—in context. The New Jim Crow was published a decade ago, so some of the figures are outdated. The incarceration rates have only gone down a tiny bit in the last ten years, though, and the general picture she paints is still highly relevant.

Alexander argues that the criminal justice system has been the primary driver of racial inequity in America since the end of the Jim Crow era (hence the book’s title). The U.S. is unique in putting so many people in jail for such long periods. We lock people up at five to ten times the rate of other industrialized countries according to the Sentencing Project, and prison spending has risen three times faster than education spending over the last three decades.

I was particularly shocked to read the stories Alexander uses to illustrate the extreme sentences that many judges are forced to hand down. Because of how sentencing laws are often structured, judges sometimes don’t have “judicial discretion”—the ability to make decisions based on their personal evaluation of the defendant. Their hands are tied, especially in drug cases. Alexander tells the story of one federal judge who broke down in tears when he was forced to sentence a man to “ten years in prison without parole for what appeared to be a minor mistake in judgment in having given a ride to a drug dealer for a meeting with an undercover agent.”

It’s clear that we need a more just approach to sentencing and more investment in Black communities and other communities of color. The good news is that support for change is growing. Although there has only been modest progress on this front since The New Jim Crow was published in 2010, a new bipartisan coalition has emerged in support of prison reform in that time. (I met with a bipartisan group to learn about the subject during a trip to Georgia in 2017.) And I am hopeful that this year’s protests for Black lives—which are now considered the largest movement in U.S. history—will go a long way toward building more public support for updating our justice system.

I hope Alexander plans on writing a follow-up to The New Jim Crow someday. The latest edition includes a new preface that touches on the Black Lives Matter movement, but it was published before the events of this summer. She’s so good at explaining the historical context behind the injustices that Black people experience every day, and I am eager to hear her thoughts on how this year might have moved us closer to a more equal society.

Behind bars

How long would you wait for love?

An American Marriage is a moving look at how incarceration changes relationships.

A couple years ago, Melinda and I visited a state prison in Georgia as part of our foundation’s work on U.S. poverty. I’d never been to a prison before, and it was an eye-opening experience.

The most memorable part was the discussion we had with some of the inmates about transitioning back into society. Although most were looking forward to leaving prison behind, some were clearly anxious about it. One man told us he was scared to re-enter society after so many years behind bars. Another mentioned that it felt like he was a car about to be dropped into the middle of a racetrack where the other cars are already going 200 miles per hour.

I couldn’t help but think about that conversation when I was reading An American Marriage by Tayari Jones. Although it’s fictional, the story is about the question at the heart of the anxiety Melinda and I saw that day: how do you rebuild your life after prison?

Our daughter Jenn recommended that we read this deeply moving story about how one incident of injustice reshapes the lives of a black couple in the South and eventually dooms their relationship. Roy and Celestial are newlyweds living in Atlanta. They seemed to have it all: good careers, a decent house, and a lot of love for one another (although their marriage wasn’t perfect).

That all changes when Roy gets falsely accused of rape and sentenced to 12 years in prison. Despite how radically this event changes their lives, Jones doesn’t spend much time on it. She devotes only five pages to Roy’s arrest and trial. Her message is clear: Roy is innocent, Celestial knows it, and neither fact matters. He’s caught up in the system regardless.

What Jones is more interested in is how incarceration changes relationships. About half of the book is letters exchanged between Roy and Celestial while he’s locked up. Although they start out sweetly, the letters become more tense as time goes on. Eventually, Celestial stops writing to Roy altogether. By the time he gets released from prison seven years early, she’s moved on. (I promise this isn’t a spoiler. It’s in the book’s jacket description!)

There’s this mythical notion that you’ll wait forever for the person you love. Penelope from the Odyssey is the classic example—she fights off potential suitors for 20 years waiting for her husband, Odysseus, to return from war.

It’s a romantic idea, but is it realistic? Jones doesn’t seem to think so. We all like to imagine we’d be Penelope in that situation, but I suspect many would end up like Celestial instead. She writes to Roy, “You may feel like you’re carrying a burden, but I shoulder a load as well.” Later, she says, “A marriage is more than your heart, it’s your life. And we are not sharing ours.”

The fact that their marriage didn’t have a fairytale ending felt realistic. Roy’s unjust incarceration—and the separation it caused—pushed on the seams that already existed in their relationship, and eventually those seams broke. Despite her decision to leave him, Celestial is a sympathetic character. You understand why she made her choice.

An American Marriage is fundamentally a story about how incarceration hurts more than just the person locked up. It’s also a reminder of how draconian our criminal justice system can be—especially for black men like Roy. Once you get sucked into that system, you’re marked for life. Everything you were or had can disappear while you’re in prison.

In a letter to his lawyer, Roy writes about how things have been difficult for Celestial but even more difficult for him. “I try to see her side of things, but it’s hard to weep for anyone who is out in the world living their dream,” he says.

Jones is such a good writer that you can’t help but empathize with Roy and Celestial. Both have been put into a super-difficult position. I obviously haven’t experienced what they go through, but the characters—and their reactions to the situation—ring true to me.

I wouldn’t say An American Marriage is a light, easy read, but it’s so well-written that you’ll find yourself sucked into it despite the heavy subject matter. If you’re looking for something thought-provoking to read this winter, you should add this one to your list.

All together now

Can romance improve your odds of survival?

Blueprint by Nicholas Christakis is a fascinating look at human behavior.

Why do we love our families?

The sociologist Nicholas Christakis would probably give way more practical answers than I would. He’d argue that our emotional connection gives us a greater incentive to work together to ensure the survival of our bloodlines. If we’re ever attacked, our larger, combined family unit is more likely to successfully defend ourselves. We’re also more likely to share food and supplies with one another, upping our chances of living through a tough winter.

In his terrific book Blueprint, Christakis explains that humans have evolved to work together and be social. Although this instinct originally developed because it made us more likely to live longer, our need to form groups has had a huge impact on human history.

Early in the book, Christakis says, “The human ability to construct societies has become an instinct. It is not just something we can do—it is something we must do.” He believes that this instinct has led to eight common traits that—with very few exceptions—you can find in every society on earth. These eight traits form what he calls the “social suite:

- Individual identity

- Love for partners and children

- Friendship

- Social networks

- Cooperation

- Preference for your own group

- Some form of hierarchy

- Social learning and teaching

Most of the book is devoted to explaining how each of these traits is found in seemingly disparate peoples, from the Roman Empire to the Turkana people of Kenya. Our world has gone from being small groups of hunter-gatherers that were closely related to the modern world where you can live in a city with millions of other people. The fact that the social suite has remained constant despite those changes is amazing.

But the social suite alone is only part of the story. If you want to explain human behavior, there’s a lot going on. You’ve got the genetics you were born with. You’ve got hormones running through the body. You’ve got your childhood and how that shaped you. And you’ve got learned behaviors—the understanding of what’s allowed and what’s not allowed that is passed to you through societal norms.

Blueprint focuses mostly on the last part. If you want a more complete picture, I recommend the book Behave by Robert Sapolsky. My older daughter suggested I read it (Sapolsky was one of her favorite professors in college), because it’s a super in-depth look at why humans act the way they do. He’s giving you a framework down to the biological and hormonal level, while Christakis focuses more on person-to-person interactions.

Behave is really long, though—nearly 700 pages!—and the incredible level of detail isn’t for everyone. It almost feels like a very well-written textbook. Blueprint is a lot more accessible for a general audience. I recommend starting with Christakis and then, if your interest in the subject is piqued, moving onto Sapolsky.

One of the things that makes Blueprint so readable is all of the fascinating examples and stories that Christakis uses. The book begins by looking at a bunch of different shipwrecks that resulted in people getting stranded on deserted islands. Each group had to develop their own form of society, and some were more successful than others. The ones that performed the best (“best” meaning that a high percentage of its people survived to be rescued) embodied some or most elements of the social suite. The societies that didn’t have these elements fell apart quickly, with several even devolving into cannibalism.

I was particularly fascinated by one section of the book where Christakis compares chimpanzees and bonobos. Chimps are super aggressive with each other and sometimes will kill members of their own group to assert dominance. Bonobos, on the other hand, are largely peaceful and playful creatures. They’re one of the only species other than humans who engage in sex for pleasure, not just for procreation purposes.

Christakis offers a couple theories for why the two types of apes are so different, even though they look so similar. Chimpanzees were more likely to share territory with gorillas and had less access to food than the bonobos, so aggressive chimps might have had a better chance to survive. Or maybe bonobo females—like humans—evolved to value cooperation over aggression when choosing a mate.

I was a little surprised to learn that the field of comparing the social behaviors of humans with other species isn’t more developed. Christakis appears to be at the frontier of this, and Blueprint only gives you a surface level understanding.

I also wish he had gone deeper on the main conclusion of his book: that every human being on earth has more in common than not. It raises big questions, like how we can leverage that commonality to get things done. Can we really get 7 billion people to work together and solve big problems like climate change? Are our similarities powerful enough to overcome the few differences we do have?

Christakis doesn’t answer these questions, but he does imply that the answer is yes by showing that we have an innate capability and need to cooperate. A lot of people are fascinated by the differences between us—but the differences are actually pretty minor compared to the similarities. In that regard, Blueprint is a fundamentally optimistic book.

I didn’t expect to finish a book about behavior feeling more hopeful, but Christakis surprised me. It’s easy to feel down reading news headlines every day about how polarized we’re becoming. Blueprint is a refreshing reminder that, when people say we’re all in this together, it’s not just a platitude—it’s evolution.

Recovery program

How to handle a national crisis

Jared Diamond explains why some nations flourish in tough times.